- Home

- Jan Richman

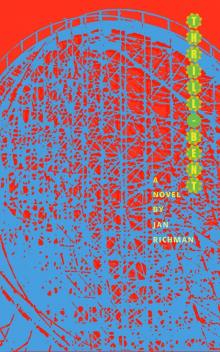

Thrill-Bent

Thrill-Bent Read online

THRILL-BENT

Tupelo Press Fiction

Lewis Buzbee, After the Goldrush, stories

Alvin Greenberg, Time Lapse, novel

Floyd Skloot, Cream of Kohrabi, stories

David Huddle, Nothing Can Make Me Do This, novel

James Friel, The Posthumous Affair, novel

Jan Richman, Thrill-Bent, novel

A

Novel

by

Jan

Richman

Thrill-Bent.

Copyright 2012 Jan Richman. All rights reserved.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Richman, Jan.

Thrill-bent : a novel / by Jan Richman. – 1st ed.

p. cm. – (Tupelo Press fiction)

ISBN 978-1-936797-20-2 (pbk. : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-1-936797-21-9 (hardcover : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-1-936797-22-6 (e-book)

1. Women journalists–Fiction. 2. Roller coasters–Fiction

3. Fathers and daughters–Fiction. 4. Tourette syndrome–Fiction.

5. Psychological fiction.

I. Title.

PS3568.I3504T75 2012

813’.54–dc23

2012038814

Cover designed by Bill Kuch.

First edition: December 2012.

Other than brief excerpts for reviews and commentaries, no part of this book may be reproduced by any means without permission of the publisher. Please address requests for reprint permission or for course-adoption discounts to:

Tupelo Press

P.O. Box 1767

243 Union Street, Eclipse Mill, Loft 305

North Adams, Massachusetts 01247

Telephone: (413) 664–9611 / Fax: (413) 664–9711

[email protected] / www.tupelopress.org

Tupelo Press is an award-winning independent literary press that publishes fine fiction, non-fiction, and poetry in books that are a joy to hold as well as read. Tupelo Press is a registered 501(c)3 non-profit organization, and we rely on public support to carry out our mission of publishing extraordinary work that may be outside the realm of the large commercial publishers. Financial donations are welcome and are tax deductible.

What people want is not the easy peaceful life that allows us to think of our unhappy condition, nor the dangers of war, nor the burdens of office, but the agitation that takes our mind off it and diverts us.

—Blaise Pascal

CONTENTS

The End of the Head

The Future Leaks Out

Jan’s Pink Triangle

Cut It Out

Sidesplitter

Where the Surf Meets the Turf

One Bad Apple

Eden’s Exit Sign

Fits & Starts

I’m the Last Splash

Lemon Tree Very Pretty

Valley of the Dolls

Aqueduct

Smuck Fog

Good Vibrations

Your Mouth Is Open

Running Leap

THRILL-BENT

The End of the Head

When the chain dogs bark and we are ratcheted up the first magnificent lift hill, even though it’s early March and there are only a handful of customers in the park, I get that feeling I always get.

Ralph doesn’t know it yet, but he is once again aiding and abetting me as a journalist. I’d called him when I found out I’d be covering the Coney Island Cyclone, knowing he’d be the perfect partner for its rickety, venerable thrills. Ralph understands pleasure, he understands Brooklyn, and I’ve never seen him refuse an opportunity to have his blood pressure raised.

This is my favorite part of any roller coaster experience: the moment of quiet premonition at the top of the hill. The thrill of elevation, of being mechanically lifted to an outpost with an aerial view of the landscape—in this case a spectacular sweep all the way from Gravesend in the north to the aquarium and Brighton Beach in the east, straight down the boardwalk in slatted increments, not to mention the ocean and the sky and the mammoth, dinosaur Parachute Jump still standing on Coney’s shore from the 1939 World’s Fair. My head is bobbing back and forth like I’m watching a fervent tennis match, and I point out to Ralph the various landmarks and components as I spot them, bouncing up and down in my seat (as much as I can bounce under the restrictive lap bar) and sniffing the increasingly thin air like it’s nitrous oxide.

Ralph doesn’t even glance around to verify my monologue’s main points; his head hangs back onto the headrest, eyes half-closed, a stoned smile smeared across his face like chocolate milk. There is a little slice of scar on his upper lip from the time he got hit in the face with a baseball bat that turns his mouth into a perpetual Elvis sneer, lifting and squaring one side ever so slightly, giving everything he says a faint sexual innuendo. Well, everything he says has a faint sexual innuendo, and the scar is a handy visual cue, reminding you that you didn’t imagine it. Ralph’s face perfectly exemplifies one aspect of what I love about the lift hill ascent: time is slowed and stretched like taffy, as though you’ve entered an anesthetic fog. I am inhaling the panoramic view at the approximate rate of a speed freak, but inside I feel as though I’d have plenty of time to paint a lazy, detailed triptych if I were so inclined. Of course, as the hill’s acme gets closer, as the idea of an impending waterfall-like drop starts to make an impression on my brain, time speeds up to a frisky trot, then breaks into a full canter as we round the top. I guess that’s what it’s like to receive a doctor’s bad news (“That lump you thought was your sternum is actually cancer”): a brief period of liquid calm before the crest of the wave of fear catches up to you.

I hold Ralph’s hand and scoot closer to him as we teeter on the tip-top of the hill. Like sex, no matter how many times you experience it, the excitement of this cliff-hanging moment never diminishes, never becomes old hat. We are going down, no question about it, everything I know about the laws of physics and human nature tells me you don’t go up into the sky and not come down—whether you break your crown or whether you come tumbling after is moot.

And so we’re off, barreling headlong into the atmosphere. I scream. I always scream. Screaming is an essential part of the package. A roller coaster with a peopled train charging down the track minus the bright, demented screams of the passengers would be like a punk show without the slamming or the stage diving—some android approximation of the real thing. Ralph doesn’t scream, but his hand closes tighter around mine and his head jumps up off the headrest into wide-eyed attention. Our stomachs, which were still hovering near the top of the hill, finally catch up to us somewhere around the first section of straight track after the drop sent us into a series of tight, elaborate torques in either direction. Ralph pulls me to him for a brief kiss, a true stolen kiss slotted in the interval between twist and shout, a lovely, warm, tongue-infused moment that takes me completely by surprise. I look into his eyes and I think I see how he will be as a very old man. I won’t know him then, of course, but I can picture very clearly how he will launch an attack on helplessness, thrust his tongue along the jutting icicle of imminent hell-freeze, rage against the dying of the light. He will be one of those lively geezers playing poker around a card table in someone’s garage with the door rolled up, catcalling to the working girls who strut their way through the neighborhood, “Looking good today, mamacita!”

After coming in third in a darts competition held at the offices of BadMouth Magazine (“NYC’s Premier Cultural Crap Detector”) last month, it seems I’m to be paid a l

iving wage to research and write about roller coasters for their annual travel issue. BadMouth’s editor-in-chief—a wee, bald man with thick black glasses—has managed to garner numerous awards by peddling obscure road-trip advice: southern catfish buffet where you’re likely to see two or more local cops at any given time, bottle-cap sculpture gardens, best pie made by someone over 100 years old, that sort of thing. He has uncanny PR skills; every year he creates spectacular buzz by getting writers to compete for stringer slots by hosting various quasi-sporting events. This year’s travel-issue theme is: Roller Coasters on the Cusp of Demolition.

So twenty of us stood around a large cork-backed US map (a.k.a. dart board) pasted on the outside of the building at Wooster and Grand, blowing into our palms—it was barely twenty degrees out, but we couldn’t wear gloves, not if we wanted maximum aim-ability. We each chose five from a list of doomed coasters; the three with the highest rates of cartographic accuracy got jobs visiting the spots their darts pierced. Hand-eye coordination has never been my strong suit, but Ralph had given me a few pointers, including a fancy clockwise wrist move. “Don’t be afraid to break out that crazy curve shot,” Betty whispered when I stepped up to the blue chalk toe-line, and she nodded meaningfully toward the left side of the map where L.A. and its environs lay. She was whispering because she didn’t want any of the other writers, most of whom thought they were Betty’s firm favorite, to hear.

Betty writes a monthly music column for BadMouth and has overseen the travel issue ever since she won the ring toss three years ago. Armed with a red bullhorn and fur-trimmed thigh-high boots, she’d been following the editor-in-chief around in circles and wishing luck to the writers, offering furtive gulps of whiskey from her back-pocket flask. But, while exuding an aura of unbiased and universal charm, Betty had a very partisan plan. She figured that there are at least two worthy roller coasters near Los Angeles, and she’d worked out a scheme to meet me in April for a little expense-accounted R & R on the West Coast. It was hard to imagine, as my fingertips bonded to the icy steel darts in my gloveless hand and my snot threatened to harden into permafrost, that in a couple of short months I could be prancing in flip-flops with Betty along the Santa Monica boardwalk.

As I pulled my first dart back to tickle my ear, I could hear Betty intoning “L! A! L! A! L! A!” under her breath. Dozens of people had gathered on the sidewalk to check out our bout of street theater—tourists, hipsters, shopgirls on their lunch hours wearing designer cloche hats—summoned by flashing cameras and Betty’s barking bullhorn. In my head, I displaced Betty’s chant with my own, the rote sequence Ralph had taught me: Aim, Cock, Accelerate, Release, Follow Through. Then, without watching where my first dart landed, I fired in rapid succession.

“Salt Lake City!” I yelled.

“Brooklyn!”

“Houston, Texas!”

“Las Vegas!”

It was so quiet on the street that I could hear the tips sink one by one into the thick layer of cork. Betty caught my eye and her gaze was like fingernails pressing into my flesh.

“Mission Beach, California!” I added, letting the last dart fly. I had looked for a coaster close to Rancho Cucamonga, the sprawling, faux-adobe suburb southeast of LA where my father has lived for the past ten years, ever since my mother died. I’ve never seen the place, but I imagine lots of gargantuan peach stucco arches and cul-de-sacs and Applebees. If my dart stuck, it would mean an expenses-paid trip to my dad’s April wedding. Mixed blessing.

Betty ran over to assess the damage. “Way to go, Janimal!” she squealed as she trotted back to hug me, the darts jutting out from between her fingers. “Santa-fucking-Monica!” She tried to high-five me with her spiky paw, but I shoved my frozen fingers back into the pockets of my coat, shoulder-bumping her instead.

The Coney Island Cyclone, a half-inch from where my first dart penetrated, is the only wooden coaster on my list to visit. Well, it isn’t even technically a wooden coaster, though it’s classified that way on roller coaster websites and blogs frequented by enthusiasts/nerds (and the occasional dilettante like me). On the Cyclone and other older, mistaken-identity (“hybrid”) coasters, laminated wooden rails have been inset with flat steel ones, and the supporting structure is also made of steel. I remember from previous rides that the Cyclone is special, almost an optical illusion. The giant, old-school construction gives the visual impression of a shaky, violent ride, like on the Santa Cruz Giant Dipper, but the actual experience is smoother and faster than the classic epileptic tempest associated with most grandpa coasters, due to its secret steel underpinnings. Given the Cyclone’s history and unique construction, I can’t believe it will be torn down any time soon. Every few years, some concerned citizen group or ambitious politician decries it a “public safety hazard” and threatens to have it condemned. Most of the other original Astroland rides have been demolished, and the surrounding area has become more seedy than family-friendly, but the Cyclone holds a fond place in the hearts of New Yorkers, cemented by its cameos in Hollywood films from The Shopworn Angel to The Wiz (and although Alvy Singer’s childhood home in Annie Hall was actually filmed beneath a now-defunct adjacent coaster, the Thunderbolt, people usually associate that movie, too, with the Cyclone). Because of its landmark status, even tenacious Mayor Giuliani, though he managed to round up homeless people and put them on trains to Secaucus, couldn’t get rid of the Cyclone. And now a(nother) lawsuit filed by neighbors has claimed that the roar of the trains is keeping them up at night.

In a flash, Ralph’s lips are yanked from mine by g-forces beyond our control. We’re sent into a pretzel-like descending helix, a continuous turn that maintains a constantly tight radius, rolling downward the whole time. It is disorienting; helices are a standard feature of any classic twister because they are sure to make you lose all sense of forward and backward motion and east-west orientation, or any idea of whether your esophagus resides above your belly button or the other way around. As we spin out of the tail of the helix and are flung down a length of track toward the ocean—if this car somehow breaks loose and jumps the track, we’ll be drinking salt water in about seven seconds—I notice a thick beam extended like a chin-up bar across the track we’re approaching. The beam seems to be supporting an element of the Cyclone’s infrastructure, a strut that holds up the hoop of track above. I can’t believe we’re going to clear it, since it’s lined up with right about where my brain will be. I have a fleeting, vivid hallucination: some sleepy roller coaster mechanic crawled up here early this morning armed with an iron joist and instructions to secure the section of track above, but he forgot his measuring tape. Eyeing the vertical distance between the beam placement and the level of the the train, he failed to factor in that the passengers would have heads. Ralph and I instinctively duck way down as we hurtle forth into imminent decapitation but, of course, the track drops suddenly just before we hit the beam, creating and canceling the optical illusion in a split second. Exhaling gratefully, I remember reading about the fine del capo (Italian for “the end of the head”) effect on some coasterhead website. There have actually been a couple of beheadings resulting from this engineering ploy, where passengers had wiggled out from under their lap bars and stood up during the ride. Also called a “head chopper,” the fine del capo usually occurs on a portion of track just before a tunnel or a covered brake run. Sometimes there’ll be ivy or a thick shrub over the entrance, to further confuse your sense of security and distance. But the Cyclone’s rusty iron beam trick was guileless and blue-collar and worked on me like a charm.

I notice a sound that hasn’t been there before: a soprano screech that melts its way through the rough wind-whip and earthquakey tremors of the ride—softly at first, then louder and higher until I realize we are slowing way down. I think I know what the sound is: it’s the sound of the trim brakes seizing the wheels underneath us. On newer roller coasters, the brakes along the track are computerized, programmed to grab the wheels should the train

exceed normal operating speeds for whatever reason. In that case, the train would gradually slow until it reached a safer designated speed, which would probably go unnoticed by all but the most discerning rider. But here on the seventy-year-old Cyclone, what we hear is more like a parrot tantrum that grows louder and wilder until we crawl, finally, to a shrieking stop at the top of the world, clinging to the narrow track, buffeted by cold air on all sides.

“What the hell?” asks Ralph, his head wobbling on his shoulders like a dashboard dog. Something has gone terribly wrong. After a couple of moments of stunned silence in the blistering wind, Ralph and I crane around to commiserate with the only other couple on the train. They are in the back car, and it’s hard to see them because we’ve already banked a turn that they have yet to come through. We are the head of the humpbacked dragon, and they are the tail: behind, below, flung off to the side. I practically dislocate my hip in the process of learning that it is not really possible to swivel under a locked lap-bar restraint.

“Hey!” I yell as loudly as I can, cranking my upper torso outside of the car. I squint to see a wild-haired woman and a man who looks like he’s trying to comfort her with there-there words we’re too far away to make out. They are huddled together in a tidy lump, except for her hair, which flies like a big ripped flag toward Manhattan.

“They can’t hear us,” says Ralph, calm as a moose. We search the ground for someone who looks like they might care. It’s hard to tell what’s going on down there, through the giant maze of peeling white latticework and loopy tracks. A few tiny people are walking around, but none seem to be stopping.

“What’s going on!” I holler. But my voice wafts away on the wind like an errant napkin, gliding over the clown-go-round at Astroland and drifting down over the pastel-painted Wonder Wheel and the faded freak show murals, landing daintily near Nathan’s Hot Dogs on the other side of the park.

Thrill-Bent

Thrill-Bent